The filmmakers behind the animated short share the power of poetry in motion.

In May of 2020, Timothy Ware-Hill added his voice to the chorus of outrage and despair that arose in response to the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, who was killed by armed white men while out for a jog in his neighborhood. Ware-Hill, a Broadway actor, decided to record himself jogging while reciting a powerful poem he had written about police brutality and systemic racism. He uploaded the video to social media and it went viral. Among those who saw it was visual-effects producer and filmmaker Arnon Manor. Within no time, the two had joined forces to collaborate on the animated short Cops and Robbers. Using Ware-Hill’s recitation of the poem as its focal point, the project brought on more than 30 artistic collaborators, resulting in a collage of animation and visual-effects styles. Cops and Robbers struck a chord with Jada Pinkett Smith, who came on as an executive producer. She, Ware-Hill, and Manor spoke to Queue about what the film means to them.

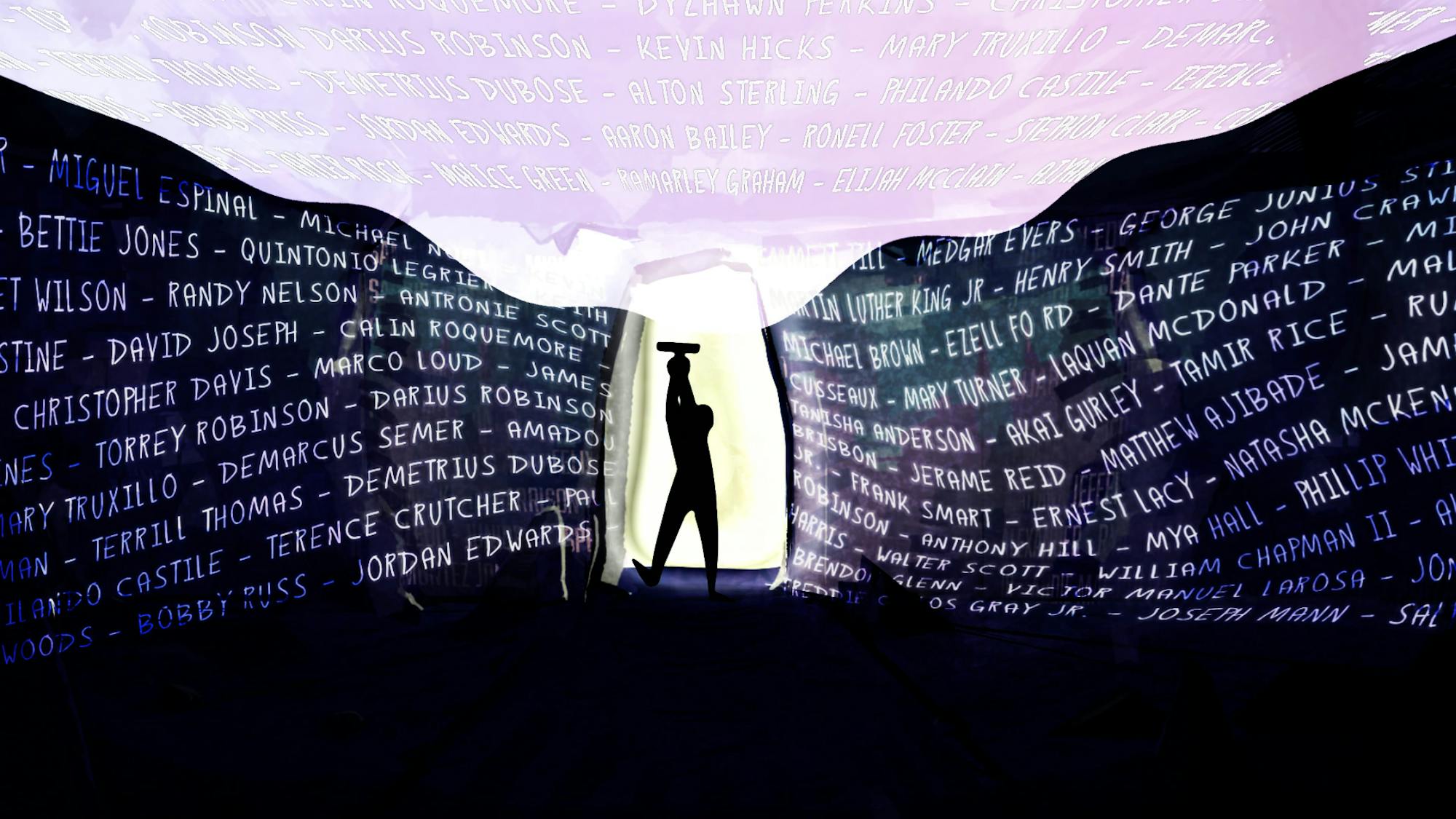

By Isaiah Shaw (Above) and Anonymous (Below)

By James A. Sims (Above) and Sisler High School (Below)

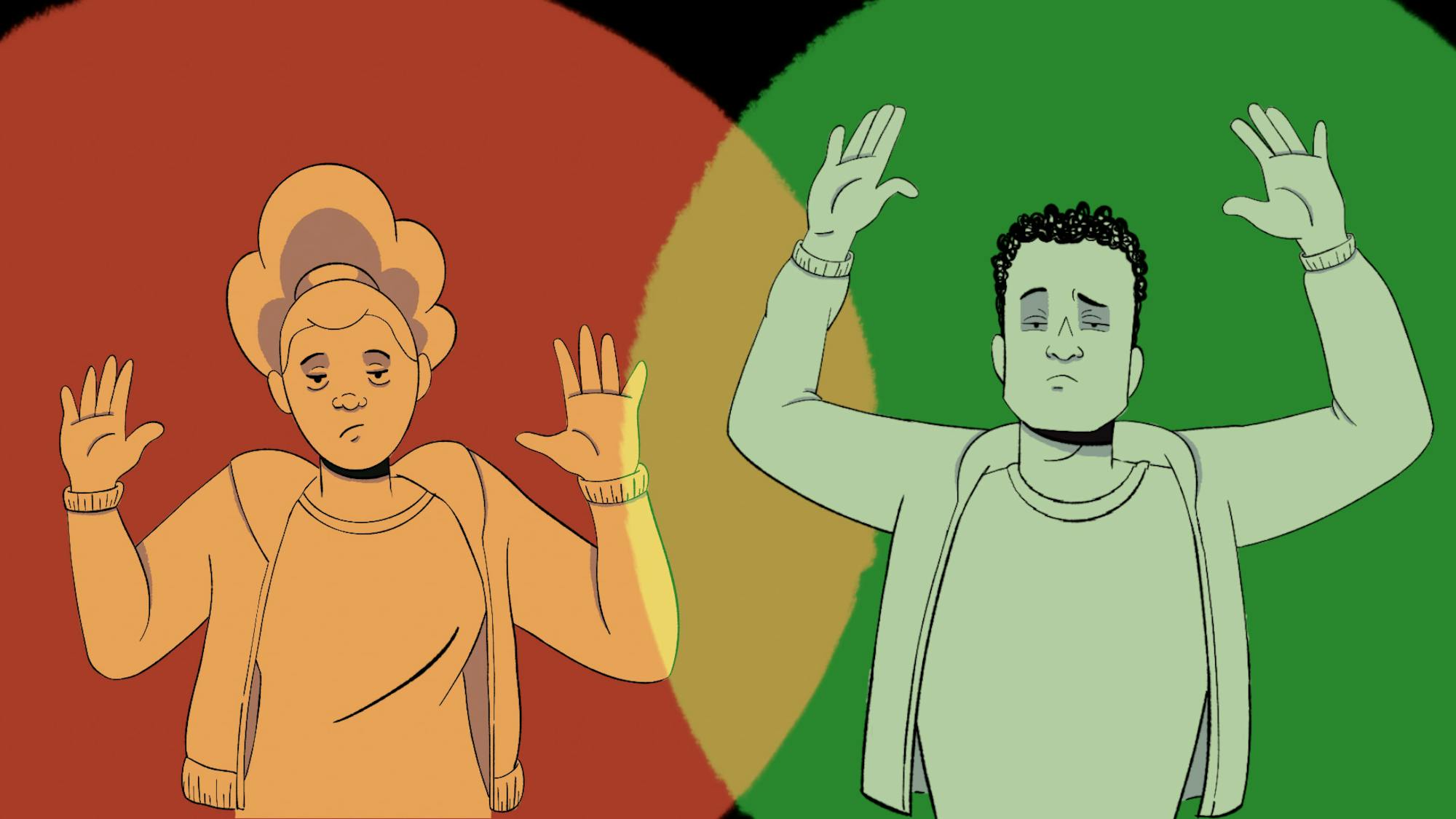

When I first saw Cops and Robbers, what was so powerful was that it had a beautiful way of communicating the voice of an entire community. When we are trying to voice our pain or our frustration, sometimes it comes from just an adult male perspective or just an adult female perspective. In Cops and Robbers, I felt the voices of every mother, every father, every sister, every brother, husband, and wife. I felt the pain and frustration of our community as a whole. Every time I watch it, it has this very piercing quality. Timothy and Arnon were able to bring a feeling of tenderness and the humanity that, for a lot of people, gets lost.

That’s one of the important aspects of this film for me: It’s so powerful that even if it’s not something that someone has experienced directly, it lends an opportunity for people to feel our frustration and our hurt and our pain in regard to what is happening. That’s one of the purposes of creating art.

By Amber L. Jones (Above) and Molecule Vfx (Below)

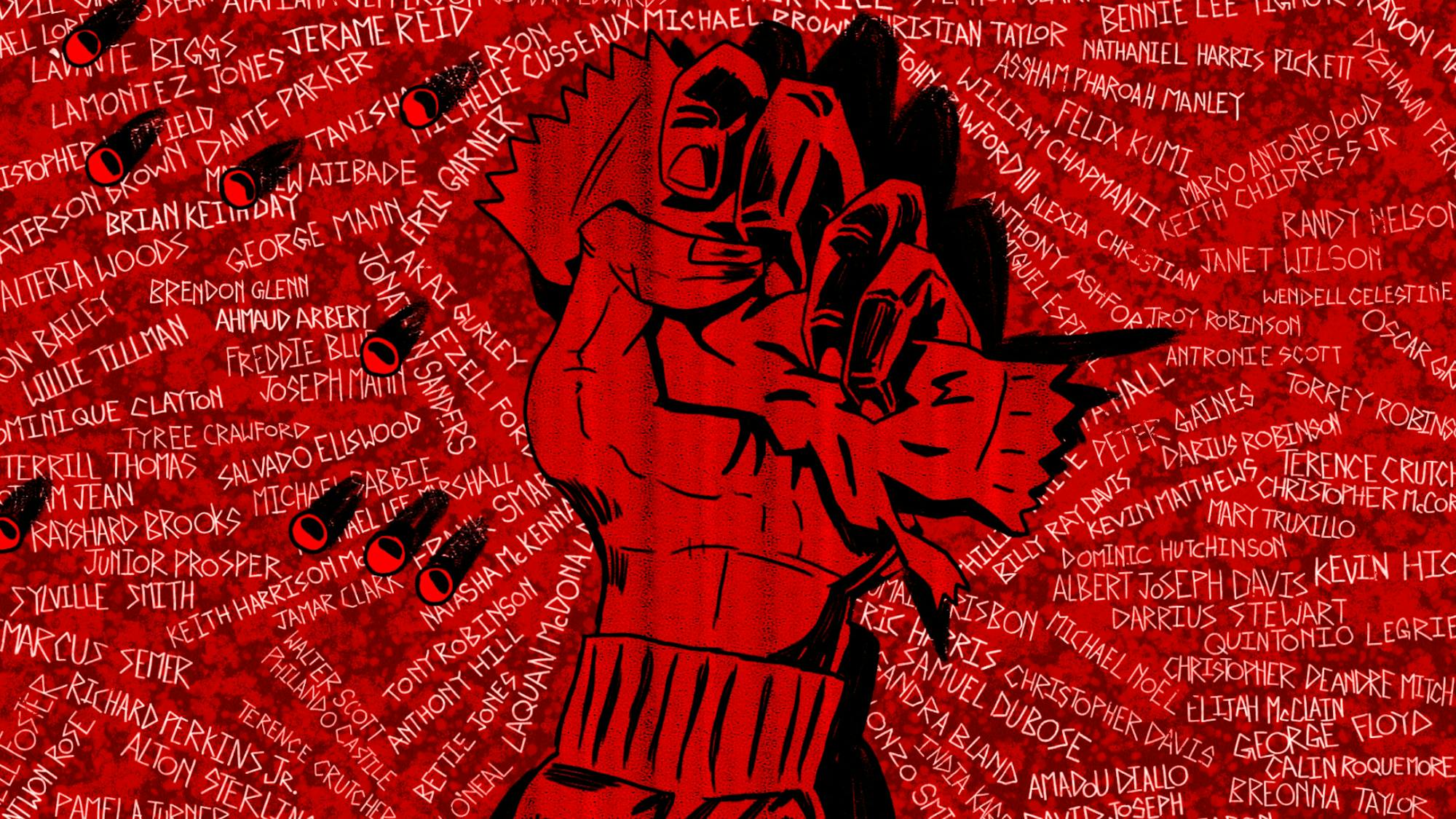

The initial, non-animated video came out of the sheer horror and frustration that the video of Ahmaud Arbery’s murder inspired, the video of his brutal slaughter by these terrorists that went after him in the street. When I saw it, it immediately sent a shock to my system — but a familiar shock, because we’ve been through this. We’ve been through this. When will this stop? How much longer must we go on having to justify our existence?

The poem actually existed maybe two years prior to when I did the initial video. The sad part is that it was still relevant. I took the poem and I decided to jog and recite it to connect it to Ahmaud’s story, to the story of this Black man just running in his neighborhood, minding his business, and getting killed. The poem asks the questions: How do we get back to a place of innocence? How do we get to a place of seeing Black people as human beings? Do cops remember being kids, when we used to just play together? There was a time when you weren’t a police officer. It wasn’t Black and Blue. It was us. Where did that disconnect happen when you joined the force? And how can you go back to that humanity that you had growing up as a kid, and still wear it with your uniform and serve to protect all people?

We say Black Lives Matter, and part of making that matter is gaining equity within our community. It’s important that the hashtag becomes more than just a hashtag, that it becomes an action, that major studios invest in Black artists and Black talent and Black creators, so that we can continue to tell our stories from our perspective. It makes a difference. Part of that equity is saying, “Hey, there is a space for you as an animator.” In Cops and Robbers, we worked with artists from all over the world, from Vancouver to Toronto, Los Angeles to New York, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Uruguay, London. And we worked with students from H.B.C.U.s.

By Atomic Arts (Above) and Molecule VFX (Below)

When we were working on concepts with all of the individual artists, we really wanted people’s emotions to come through. We weren’t necessarily looking for high-end, finished animation. At times we actually told people, “You know that drawing that we did originally that just had this raw emotion? Go back to that. Forget about that clean version.” A lot of it was just directing them to pour their hearts and souls into it. This is free of any constraints. What do you feel? What are your emotions about this?

How much longer must we go on having to justify our existence?

Timothy Ware-Hill