“I’m thinking of ending things.” That unsolicited thought lodges itself in the mind of a young woman as she accompanies her boyfriend on the drive out to his parents’ remote farm. The words pursue her through the uncanny winter evening. Before long, she’s fallen down an existential rabbit hole, where memory and identity are illusory, time itself slippery.

The careful equation of philosophy and absurdity in i’m thinking of ending things is characteristic of writer-director Charlie Kaufman. The Academy Award winner established himself as a Hollywood visionary with screenplays for Adaptation, Being John Malkovich, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and Synecdoche, New York. Adapted from author Iain Reid’s acclaimed debut novel of the same name, i’m thinking of ending things builds on Kaufman’s best-loved work, assembling a cipher between the real and the surreal.

The contours follow the broad strokes of Reid’s enigmatic tale: Irish actress Jessie Buckley delivers a finely calibrated performance as the unnamed protagonist contemplating an end to her relationship with boyfriend Jake (Jesse Plemons) during a trip to visit his parents (Toni Collette and David Thewlis). As the film plunges headlong into the poetic, Kaufman’s distinctive creative vision takes hold.

Jesse Plemons, Jessie Buckley, Toni Collette, and David Thewlis

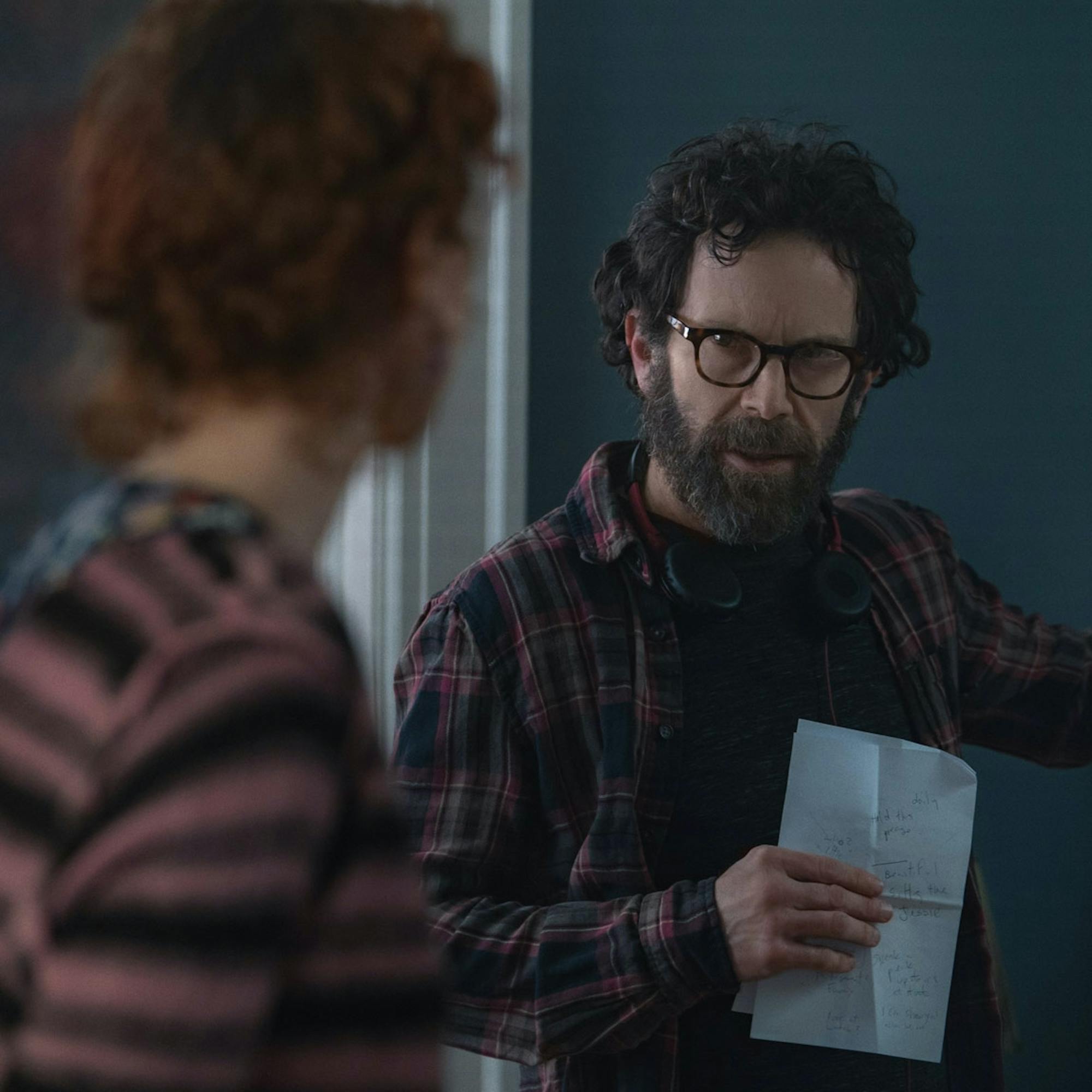

Jesse Plemons and Charlie Kaufman

Photograph by Mary Cybulski

Iain Reid: So, Charlie, we can maybe go back a few years to when you and I first started talking . . .

Charlie Kaufman: I contacted you. I read the book, and I remember calling my agent. I guess she got me your information, and I called you. Were you aware that I was going to call?

IR: Yeah, because my agent had been sending the book around a little bit. I’d never had any kind of interaction with the film world, so I was going through that for the first time. Most of the calls had been with multiple producers at a time. After doing a few of those that felt, I would say, disingenuous, my agent sent me an email saying, “Would you have time next week to talk to Charlie Kaufman?” I have a little desk calendar, and I remember looking down at it, and it was literally blank. I was like, “Yeah, I could probably manage to do that.”

What I liked was that it was just you and me on the call. We talked for five or ten minutes about the book, and then we talked for a while about a variety of things. It was really casual.

CK: And then we met each other in Reykjavik. You invited me to stay in your guesthouse there. I remember you said you were anxious about what it was going to be like to be stuck in this place with this person that you didn’t know — and I’m always anxious like that. But it was very comfortable, I thought.

. . . There’s no one else who I would want to do this.

Iain Reid, on Charlie Kaufman

IR: Yeah. Some of the conversations we’d had before meeting in person confirmed that we had some similarities in our personalities, in our interests, and in the kinds of things we’re drawn to as far as our own work. That first call, even, I remember talking about different films and music and books — just getting to know each other. That made me more excited about the prospect of this project. The other conversations I’d had, it almost felt like some of those producers hadn’t even read the book. It was like, “Oh, maybe we can take elements of this story and make a horror movie or something.” But I knew that you’d read it, that there were parts that had resonated with you.

CK: It was very important to me that you knew that this might take a while before it actually happened, if it ever happened. Once I engage like I did with you, then I start to feel a responsibility that I don’t feel if it’s all sort of vague and abstract. Historically, I’ve found that I get interested in something, and I call my agent and find out if it’s been optioned, then I get cold feet and I move away from it. The fact that I knew you at that point made it more difficult for me to back away from it.

IR: In my mind, it was like, There’s no one else who I would want to do this. It was never in my mind that this was going to be adapted into a film, anyway. I didn’t think that was a possibility, but I liked your work, I was a fan of yours. Then I liked you as a person after we talked. I didn’t want to pressure you, obviously, but there was something about the way you had responded to the material and the discussions we’d had . . . I just felt like nothing else would equal that. I wanted to keep that possibility open.

CK: We also had a lot of conversations about casting. We pretty much hired everybody in Hollywood, and Europe, and Canada. One of my favorite things is casting work — or even imagining casting stuff — because there are endless possibilities.

Jessie Buckley and Charlie Kaufman

Photograph by Mary Cybulski

Jessie Buckley

IR: We did that with music a bit, too. I remember sending lots of music back and forth that seemed to convey the tone that we were thinking about. We both knew this wasn’t a horror movie. It’s been interesting for me to see how the book gets marketed sometimes as a thriller, sometimes as horror. I’ve never really thought of it as a thriller. To me, it’s just a literary novel. It’s unsettling, and it’s philosophical. You and I both understood it’s not really at its best if it’s just a generic horror movie.

CK: If you move into a genre, there are conventions that you have to attend to, and I didn’t think that was going to serve the material.

IR: Exactly. Like jump scares and gore — you and I talked about how for us, even as viewers, that’s less appealing. Stuff that truly makes me unsettled or makes me think about my own life — that is interesting. I’ve always thought of the book as being about questions more than anything, and not really about any particular answers.

CK: You said that you felt it was a philosophical book, not a horror book.

I feel like any work of art, any creative work, exists as an interaction between the person who created it and the person who’s experiencing it.

Charlie Kaufman

IR: Yeah, which is why there’s so much dialogue, especially at the beginning. People talking about the end of the book have sometimes said, “Oh, I figured out the twist halfway through.” In my mind, I’m like, What do you mean, the twist? That’s not how I set out to write it. If the end is surprising to a reader, I like that. But again, this isn’t a psychological thriller with a twist ending. It’s just a book, and it tries to tell a story in a way that’s a little bit more unusual. I feel like the film also does that. It’s not necessarily about the end; it’s about everything that’s happening and the questions that arise.

CK: I wanted to address that concern of the twist ending by not making it a twist ending. Movies are different, in my estimation, than books, in that you’re taking something that can be enigmatic on a page, and you’re making it concrete: Now you’ve got actors and a set, and you’re saying, “This is what it looks like.”

IR: It’s now solidified.

CK: It’s funny, people don’t get the ending of your book sometimes. I’ve read things online where it’s like, “Well, what happened? I don’t understand.” It’s curious.

Jessie Buckley and Jesse Plemons

Photograph by Mary Cybulski

IR: I always say — and again, I think this is something that you and I are similarly aligned on — that people can interpret it however they want. They have as much authority as I do to say what it’s about. People have been quite emotional with me about what the ending means to them, and they want to know what it means to me. Sometimes they almost want to argue with me: “This is what it has to mean.” And I think, Well, it does for you, and that’s valid, but for me, it means something very specific, and that’s O.K. That probably is the same with the film.

CK: I feel like any work of art, any creative work, exists as an interaction between the person who created it and the person who’s experiencing it. They bring to it what resonates with them based on their life experiences. If you spoon-feed stuff to people, then you don’t allow for that process; therefore, it’s a lesser experience.

IR: The other thing is the length of the book. It’s obviously a fairly contained story. I had in mind that there would be some potential for rereading, and that the second reading of the book would be different. I love rereading books; I do it often. So I thought if you’re asking someone to do that, you can make it a little bit easier by making it short, by making a 200-page book. I do feel like the movie has that in some ways. That was my feeling right away: I wanted to watch it again, knowing it would be a different experience.

CK: That was the intention. And I salute you on the length of your book. I have this very, very long book [Antkind], but I think you’re right: I will write a shorter one next time.

IR: I like to use the meal analogy: Sometimes you want to have a massive Thanksgiving dinner with all the trimmings. To me, that’s like a long book. Then sometimes you just want a tiny piece of sushi that you eat and it’s delicious, or a sauce that’s been reduced onto one spoon. They’re both good. They both have a place.