A Chicago-based arts nonprofit finds inspiration in A Love Song for Latasha.

“The most disrespected person in America is the Black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the Black woman. The most neglected person in America is the Black woman.”

Malcolm X uttered these words in 1962. Almost 60 years have passed, and they still ring true. As our country reels from a pandemic that disproportionately impacts communities of color, as the world waits to see how the social unrest of 2020 will inspire change in 2021, names like Michelle Cusseaux, Sandra Bland, Rekia Boyd, and Natasha McKenna no longer appear in the headlines — if they ever did. America’s collective attention ebbs even for Breonna Taylor, whose killing by Louisville police officers was one of the sparks that ignited the Black Lives Matter protests in the spring and summer.

The ways in which Black women and girls are forgotten and erased are not new. But neither are the ways in which Black women and girls support and advocate for themselves, ensuring that their sisters’ legacies live on even when it’s no longer popular to say their names.

Untitled Portrait II

By Angelina Cofer

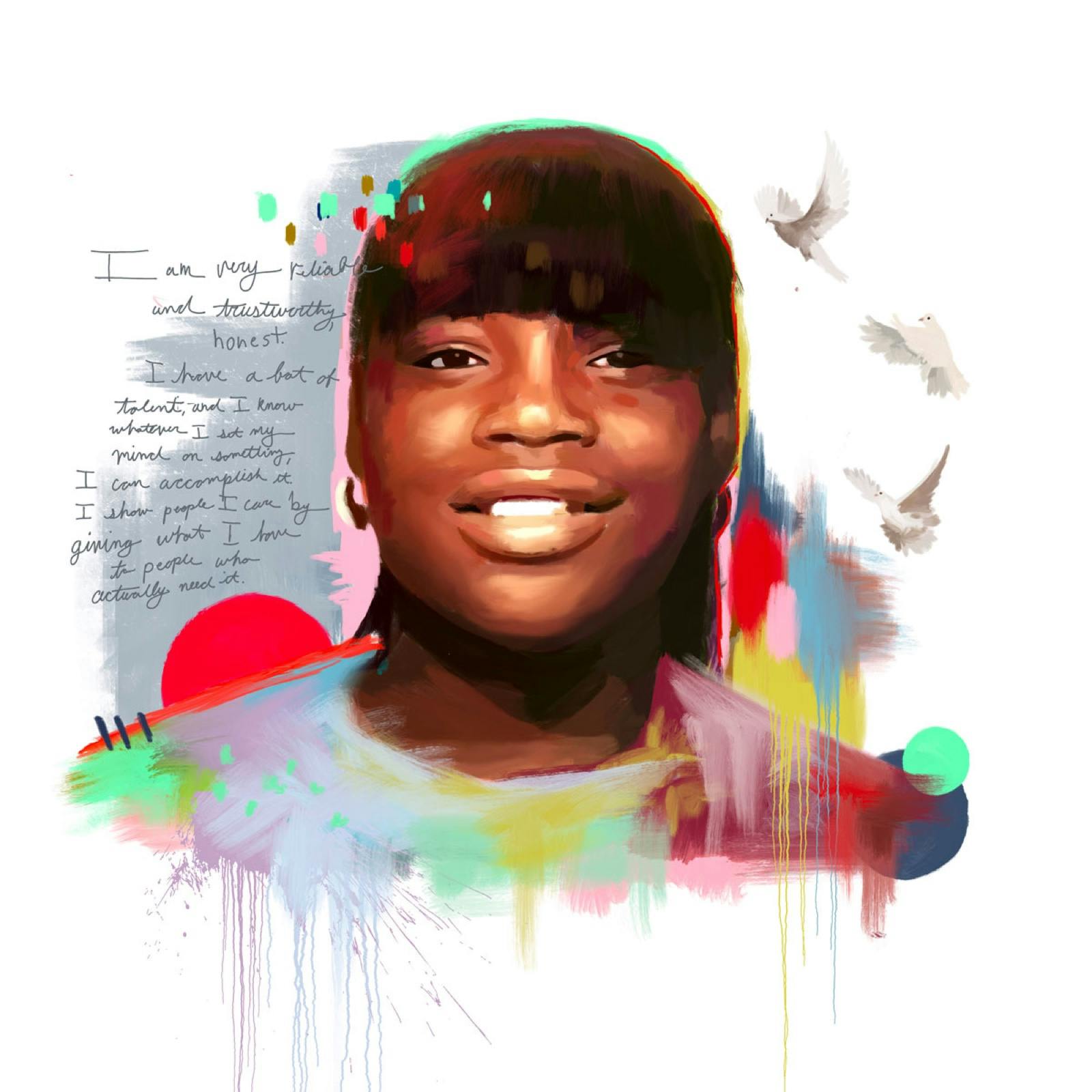

Black Girl Magic

By Azariah Baker

Therein lies the power of We Sing A Black Girl’s Song, a virtual art exhibition curated by the Chicago-based nonprofit A Long Walk Home in collaboration with Netflix. The project takes its inspiration from Sophia Nahli Allison’s short documentary film A Love Song for Latasha.

Through a Black feminist approach, A Long Walk Home fosters artist-activists and advocates for gender equity and racial justice, with an emphasis on amplifying the voices of marginalized girls and women. Over the years, the collective has provided opportunities for education, creativity, activism, and healing; its after-school programs, summer trainings, and creative endeavors intersect with other campaigns against racial, sexual, and domestic violence.

Scheherazade Tillet co-founded the organization with her sister, Salamishah, in 2003, and today serves as its executive director. She says she immediately recognized A Love Song for Latasha as an extension of the work she was already doing. The documentary honors Latasha Harlins, who was just 15 years old when she was murdered by a convenience store owner — over a bottle of orange juice — in South Central Los Angeles in 1991. Her death was an instigating force in the city’s historic uprising the following year.

In a still from A Love Song for Latasha, a market stands in for Empire Liquor, where Latasha Harlins was murdered in 1991

Image Courtesy of Netflix

A still image from A Love Song for Latasha shows one of the young faces featured in the film

Image Courtesy of Netflix

The film takes an unconventional approach. Allison, its director, says she “wanted to create a film that surpassed time and space and existed between multiple dimensions — the spirit world and the physical world, dreams and reality,” while also creating “an archive that presented an authentic representation of who Latasha was and who she could’ve been.”

She brought in young people to portray the essence of Latasha and her neighbors, and narration is provided by Latasha’s cousin, Shinese Harlins, and her best friend, Tybie O’Bard. “As a native of South Central L.A., I knew the only people who should tell her story were those closest to her,” Allison explains. “I chose to center Latasha’s cousin and best friend as a way to dismantle the adultification of Black girls and honor the memories and experiences of Black girls.”

Last fall, A Long Walk Home held a virtual screening and conversation for participants in its Girl/Friends Leadership Institute, which empowers Black girls and young women from Chicago to find their voices and advocate for justice in their communities. With clinical therapists on hand, the group unpacked their responses to the film and to Latasha’s story.

“I was in awe of how all these young people [in the film] represented Latasha, and how that resonated with our work,” Tillet says. “It just touched me — not fixating on tragedy, but on life.”

As for the response from the Girl/Friends participants: “They felt like they were Latasha,” Tillet says. “I knew by how much it brought up for them that the film meant something. One of our young people said, ‘I would like for other people to learn about her and also make art to remember her by.’”

I want black girls to know their power.

Sophia Nahli Allison

Taking that direction, Tillet tapped a member of A Long Walk Home’s board, Leah Gipson, a visual and sound artist, art therapist, and assistant professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Together, they co-curated a response to the film, inviting the Girl/Friends to use their art — photography, creative writing, mixed-media portraiture — to reflect on their lives as homages to and extensions of Latasha’s. In this way, We Sing A Black Girl’s Song was born.

Created over the course of a couple months in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, the exhibition explores grief, girlhood, loss, and remembrance. It takes its name, in part, from Ntozake Shange’s choreopoem for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, in which Shange begs, “somebody / anybody sing a black girl’s song.” The work on display is a reflection of how, more often than not, Black women and girls see themselves and their sisters in ways wholly different from how they are seen by others.

May I Have A Seat At The Table?

By Amachi Smith-Hill

Stand By Me

By Danielle Nolen

The exhibit also represents a call to action, as both Tillet and Gipson note when they discuss 15-year-old Azariah Baker’s poem “Ode to my Girl/Friends.” “Her writing, the first in the exhibit, really speaks to the fact that our girls can make those connections sometimes when adults cannot,” Gipson says. “They see the links between George Floyd’s death and Rekia Boyd’s. They can also see the links between the kinds of violence that you would see on camera and the kinds of violence that impact girls, gender non-conforming youth, and trans youth behind closed doors.”

“Black girls deserve a right to their bodies,” Baker writes, “a body that they can call their property, not a political playground / where their heartstrings will be pulled / and pushed like children on swing sets / black girls deserve to be children.”

For her part, Allison hopes that her film and the exhibition can serve as catalysts for change. “I want audiences to interrogate what it means to witness and exploit Black trauma,” she says. “I want Black girls to know their power, to remember their ancestral brilliance. I want them to create their own archive and to reclaim their stories. I want Black girls to radically build a new future for themselves.”